It’s notoriously tough to land a political blow on Donald Trump, but California congressman Ro Khanna is one of the few Democrats who have had some success. This summer, by relentlessly agitating for the release of the Epstein files, Khanna drove a wedge between the President and some of his supporters. In July, the furor grew so clamorous that House speaker Mike Johnson sent Congress into recess early to help his party avoid some potentially damaging Epstein-related votes.

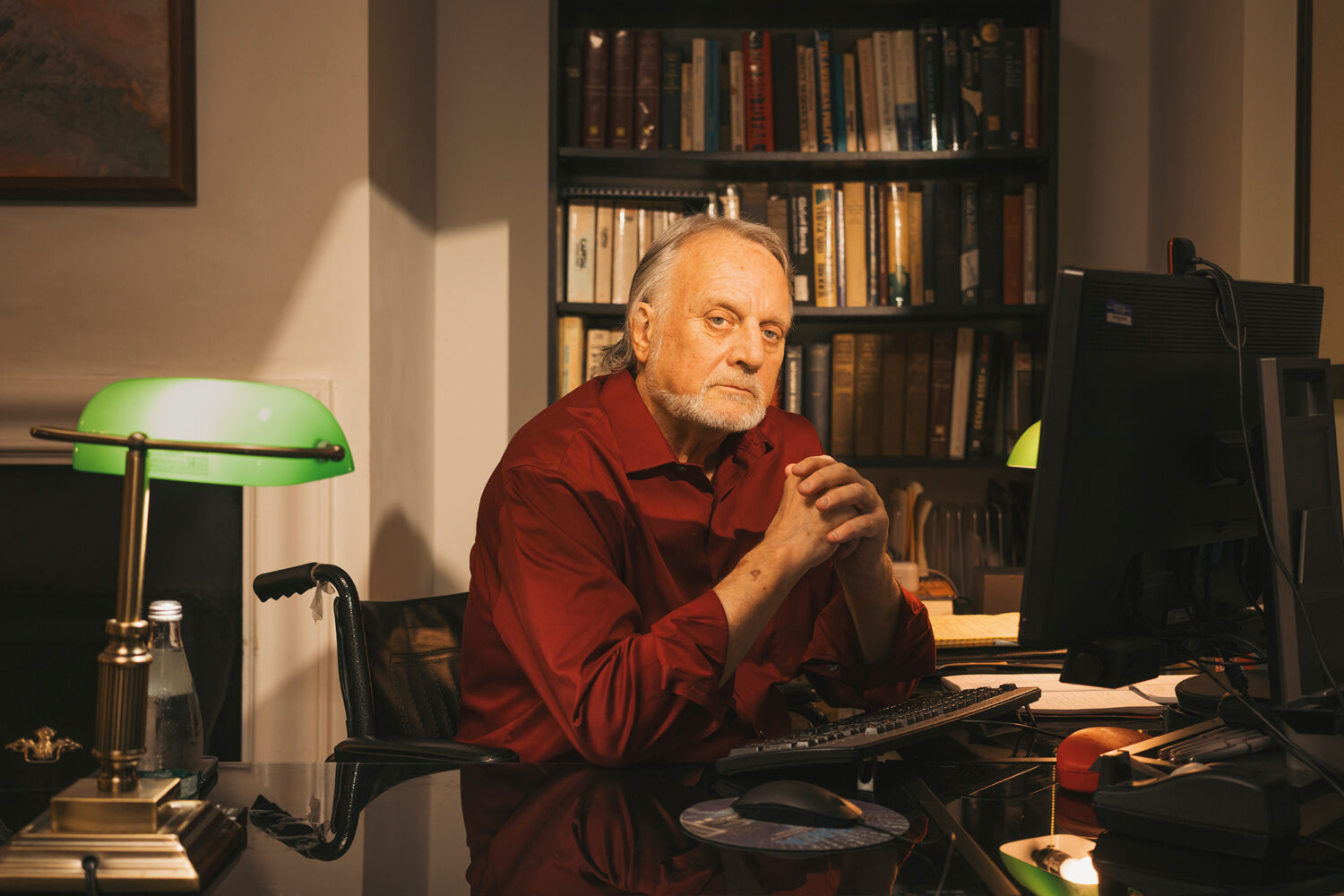

But Khanna has more to offer than point-scoring. Despite representing deep-pocketed Silicon Valley, he’s embraced an agenda of economic populism (taxing the rich, Medicare for All) while also preaching an “economic patriotism” that involves re-industrializing the hollowed-out heartland. A co-chair of Bernie Sanders’s 2020 campaign for President, Khanna has been heralded as a “rising Democratic star” (New York magazine) and a possible “future of the Democratic party” (the Atlantic). He also appears to be running for President in 2028. Our interview, at his office in the Cannon building, happened the week after Charlie Kirk was murdered, right after ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel. We started late because Khanna was tied up in the House Oversight Committee trying to subpoena the chairman of the FCC.

Recently, you’ve been talking a lot about Jeffrey Epstein. Why is that a focus right now?

First, it’s about standing with survivors. I’ve met personally some of the women who were raped and abused at the age of 13 or 14. They have been silenced and discarded by our country for over a decade, and anyone who hears their stories is determined to fight for accountability. And it’s beyond Epstein—we have a culture of abuse of girls and women, and we need to grapple with that. Finally, it’s an issue of the rich and powerful controlling our government with impunity—that many people think our government doesn’t work for them, that their government has different rules for the rich and powerful. We need to rebuild trust with the American people.

But you’re the kind of Democrat who believes that the party should primarily be talking about economics. Is Epstein a distraction?

Epstein is about building trust in government. Yes, our fundamental issue as a country is how to tackle the economic divide that’s tearing us apart. And I have a vision for that, but it involves the government. Well, how can we lead if people don’t trust us? When John F. Kennedy was President and talking about going to the moon, trust in government was close to 80 percent. Now it’s around 20 percent. So Epstein, to me, is about showing the American people that the government can be trusted, that we’re on their side.

Politically, why has Epstein been such an effective attack on Trump?

Because it’s not an attack on Trump. It’s working precisely for that reason. A lot of other things get discounted as “There they go again, attacking Trump,” but here we have Marjorie Taylor Greene, Nancy Mace, Lauren Boebert, Thomas Massie. It’s a broad coalition. That’s why this is working with some MAGA voters, because they’re saying, “Okay, he’s not doing this just to score points, he’s doing this to root out corruption in government.”

In general, it’s been hard for Democrats to wound Trump politically. What should the party be doing?

I think we have to talk about Trump as if he’s a lame duck. He’s an [almost] 80-year-old President, a 1980s guy with 19th-century policies. We need to move beyond the Trump era. We need to build a coalition that includes some of his voters around an economic vision of success for every family and community in this country. We should say that we have a more forward-looking, contemporary vision than Trump.

And I should say that while we have to put Trump in the rearview mirror, as opposed to dwelling on all of his behavior, we do need to speak out with great vigor against his unconstitutional actions. We shouldn’t be naive about his assaults on the First Amendment and universities, about his militarizing the streets and ending vaccines. We need Congress to reclaim our Article I role. We’re not lackeys for Trump and Vance. We’ve got to stand up for our own dignity.

You grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, which is a notably swingy area. How did that shape your understanding of politics?

It shaped everything about my politics. The two influences on my politics are my grandfather—who spent four years in jail alongside Gandhi as part of India’s independence movement—and my teachers and friends and neighbors in Bucks County. Bucks County gave me a fundamental hope about this country. It gave me a sense of incredible belief in the possibility of democracy.

I had a very traditional upbringing. I collected baseball cards. I watched Rocky movies with my friends. We played street hockey and went to Phillies games. The street where I grew up was economically mixed. My father was an engineer, my mom a teacher’s assistant—and on our street, we had the kids of an electrician, a nurse, an HVAC technician, and then we all went to the one house that had the pool, and that person’s father was a vice president at a company. But we all played together. And a lot of times when I’m thinking about what I’m trying to articulate with policies, I think about what would the kids I grew up with think about this? How would they talk about it?

But why is your takeaway a faith in American democracy and not just “I had a great childhood”?

Well, because I was participating in American democracy. I used to write articles in the Bucks County Courier Times—they published my first op-ed when I was 14 years old, and I was like, “Wow, they’re publishing an Indian immigrant kid’s views on the Gulf War.” I spoke out at school-board meetings. I would go often to Independence Hall when we had visitors from other parts of the country, to Valley Forge. There was such a sense of participating in the democratic process, of understanding American history. I think that’s where I got my political bug. Obviously, my grandfather had something to do with it, but it was Bucks County that shaped my interest in politics.

You call yourself a “progressive capitalist,” which means promoting economic growth–including in economically depressed regions–while also redistributing wealth. Why is this your biggest priority?

Because I think if we don’t address that, we can’t heal this country. Because if we want to have a multiracial democracy, a foundational aspect of that is having people feel that modernity is working for them. Trump is saying life used to be better in 1965—and I know for a lot of people, they may agree. It’s harder now, especially if you’re in a one-income family, to be able to afford childcare and healthcare and housing. Trump is saying the olden days were better—but the olden days also happened to be less diverse. If we want to win the argument that the future of our country is a cohesive, multiracial democracy—that immigrants enrich this nation—then we need to argue that the future is better economically, and that means we have to tackle the economic divide.

What do your Silicon Valley constituents gain when you promote economic growth outside of your district, in places like the Rust Belt?

There are two things I say to them. One is it’s an anti-revolution tax. You should pay more so that we don’t have nativism, a total rejection of globalization, a rejection of technology and innovation, a total tearing-down of the economic system. In a way, it’s FDR’s argument—he said that to save capitalism from itself, we needed a New Deal.

But secondly, if you truly want to be competitive with China, we need a strong, vibrant workforce and democracy. And if you have areas of the country that have resentment and grievance, that’s going to lead to a polarized politics, to less support for universities and science. It’s also going to lead to less people being able to do the trades and produce things and be innovative. So then it’s going to be hard for us, long term, to compete.

You say that Silicon Valley embodies the promise and exceptionalism of America. Why is tech valuable to the United States right now?

I mean, mRNA was an enormous advance that helped lead to the Covid vaccine being manufactured in such a short time; it’s leading to possible universal vaccines for the flu, for strep throat. The ability to have more biologics because of AI is going to be incredible. The ability to have more tailored education because of AI will be incredible. Our communications are much better. Our ability to get knowledge is much better. For those who are concerned about the killings in Gaza, we probably wouldn’t know about a lot of it if it weren’t for social media.

Now, does that mean that [these social-media platforms] don’t have problems? Of course they have problems. They have been horrific engines of radicalization, they’re feeding junk to young girls on eating disorders and suicidal thoughts. We need to have regulations of social media. We need to have regulations of AI. But in terms of advancing science, advancing health, advancing human interaction and knowledge, they have been incredible.

A lot of the folks who have founded and work at these companies are your constituents and donors. How can voters trust you to regulate them?

Well, I have. In 2018, Tim Berners-Lee and I called for an Internet Bill of Rights. I’ve said you should own your data, that there should be a data dividend of about 500 bucks for the use of your data, that we need to make sure that there’s transparency on algorithms, that there should not be bots, that we need to have kids protected with a standard of care. I’ve taken on these tech companies in places where they disagree with me.

But none of that is law. People don’t get a dividend for the use of their data, there aren’t robust protections for children online–I could go on, but this stuff remains relatively unregulated.

Yeah, I think that’s been a big failing of the Congress, but that’s partly because of the technological illiteracy in the governing class. You need people who understand this technology to be able to stand up to the technologists and regulate it. And our Presidents and leaders have not prioritized technological regulation when I proposed it.

What do you think the most impactful tech regulation would be?

Owning your own data, so that the tech companies can’t harness all this data and then target people in ways that will radicalize them with custom content. Secondly, there needs to be transparency about algorithms and giving people control over what they’re seeing—so that if they want to see things chronologically, as opposed to having an algorithm feed them things, they can. Third, the Kids Online Safety Act. I mean, there should be age verification. There should be a standard of harm for what you’re doing to kids. Fourth, getting rid of bots, because most of the hate online comes from the bots.

When you advocate for these regulations, what do tech leaders in your district say?

They say, “Well, the [regulatory] framework isn’t there—have Congress do the framework.” And I say, “What can you do voluntarily?” And they say, “Voluntarily? We could be sued because it’d be a violation of free speech.” Some of it is excuses. But ultimately, you’re not going to get tech companies to self-regulate. If tech companies have to get rid of all the bots and their user count goes down, then their stock may suffer. So why would they do that? I’m not naive [enough] to think that we can count on the benevolence of tech companies to regulate themselves. We need federal action to do that.

What is the policy position of yours that most upsets big tech?

The wealth tax. They don’t want to pay a 2- or 3-percent wealth tax on their money. That’s probably the one they disagree with the most. I think some of the Internet Bill of Rights they would be fine with.

You and Elon Musk are acquainted. He makes cars in your district, he blurbed one of your books. What does his political transformation say about the current state of things?

I think it speaks to some of the libertarian Silicon Valley technologists moving to Trump, but I think many of them have been disappointed, including Musk. They’re horrified by the tariffs, they’re horrified by the attacks on universities and international students. They’re horrified by the anti-vaccine stuff. But they’re not willing to speak as much publicly because they don’t want to be targeted. We have an opportunity as Democrats to win some of those entrepreneurs and technologists back, but they’re not sold on the Democrats yet.

So what do Democrats do to sell tech leaders–and Americans more broadly–on the party?

We need a vision to inspire America. We need a new national mission, and our national mission should be the economic development of every community in America. New factories, new trade schools, new AI academies, new healthcare centers. We should work towards the economic revival of America—build a strong, vibrant economy that allows people to feel that the American dream is coming back, that their kids are going to have a better future, that the country is going to be humming again, moving again, vital again, united again.

That might strike some people as very nostalgic, or even naive. Like, is Akron, Ohio, going to be a thriving middle-class community again?

I think it can. I’m not saying that it’s going to have trillion-dollar companies like Silicon Valley. That would be naive. But could it be a strong, vibrant middle-class community? Absolutely. You look at places like Pittsburgh, or the Research Triangle, that have transformed. You look at places in the South that have attracted foreign investment and transformed. It’s certainly possible. America’s capacity for resilience and reinvention is extraordinary.

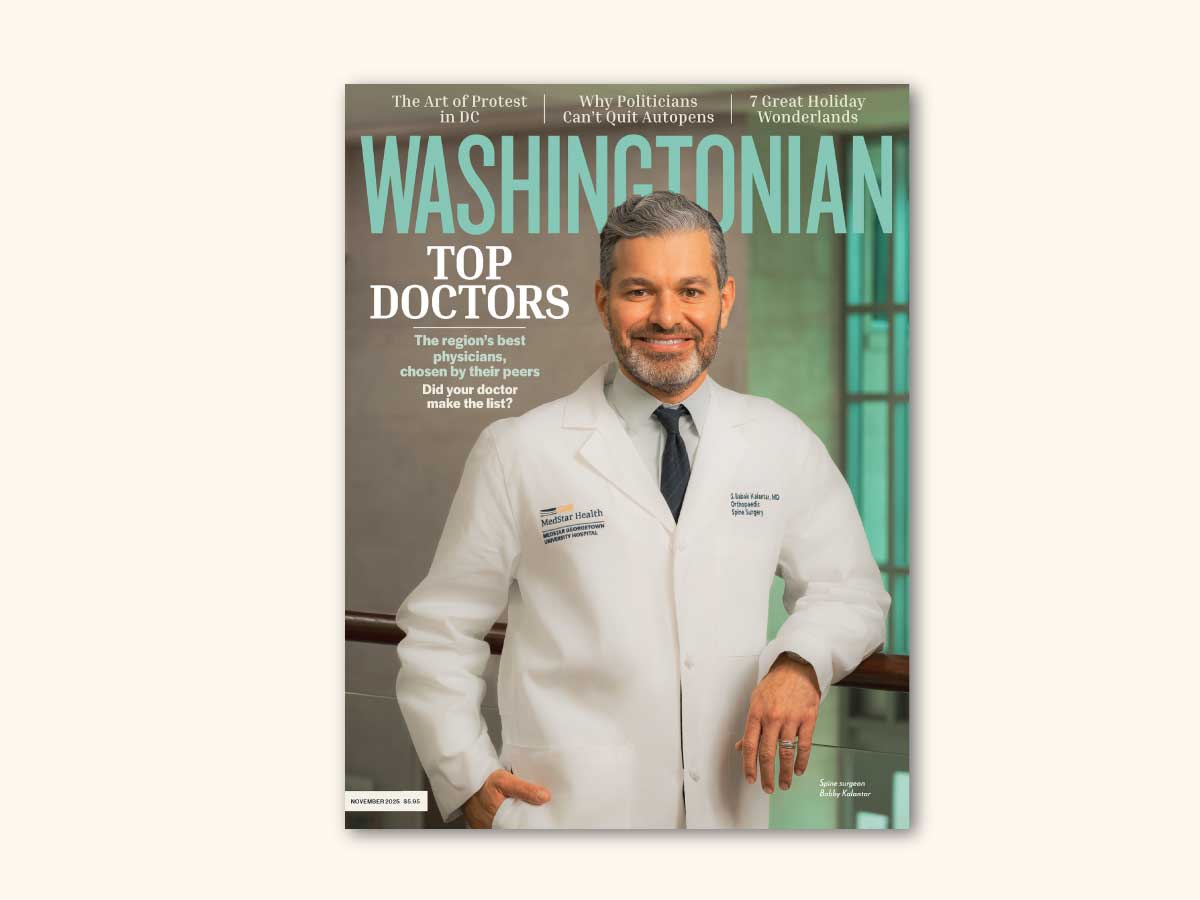

This article appears in the November 2025 issue of Washingtonian.